CAPE FEAR (1991) // "Return To Cape Fear" |

Return to CAPE FEAR: |  |

|

FT. LAUDERDALE, Fla. — The sprawling two-story house, with white columns out front and a greenhouse-turned-artist's studio in the rear, urges a feeling of quiet dread, even when the sun is shining. A perfect setting for a film about a seemingly happy family terrorized by an ex-con, a menacing figure returning from an anguished past. In fact, with an actor walking around the yard with a hole in his head and blood draining down his shirt, it could be the setting for the remake of NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD. Instead, it is one of the sets for Martin Scorsese's remake of the 1962 thriller CAPE FEAR which starred Gregory Peck, Robert Mitchum and Polly Bergen. The new version stars Nick Nolte, Robert De Niro and Jessica Lange. Florida is standing in for the Carolinas, which was the setting in the John D. MacDonald novel, "The Executioners," from which both films are adapted. The film company has set up an ad-hoc home base at the site of this key location, a 10-acre estate substituting for the home of the Bowdens, who were played by Peck and Bergen in the first film and are being played by Nolte and Lange in this one. De Niro takes over Mitchum's character of Max Cady, an ex-con who comes to exact revenge on Sam Bowden, the lawyer whose testimony years earlier sent him to prison. If this doesn't sound much like either GOODFELLAS — for which Scorsese just received an Oscar nomination) or MEAN STREETS it's not supposed to. Scorsese, at the urging of De Niro and Steven Spielberg, is using his bag of cinematic tricks on the film genre he has always loved but never attempted: the thriller. "I like looking at old Val Lewton films a lot," Scorsese says, rattling off a list of Lewton films that include I WALKED WITH A ZOMBIE, CAT PEOPLE and ISLE OF THE DEAD. "I just like the look of them; they're so beautiful. It's getting to the point now where there are certain titles that become like paintings. I put on some old films on video or laser or even on 16mm, and they run like music to me. They're like old family fnends. I feel at home with them." Scorsese was also a big fan of J. Lee Thompson's CAPE FEAR, but saw the remake as an opportunity to see what it must have been like in the old studio days when those great films were being made. "I just want to challenge myself," he says during a break from shooting outside the gloomy two-story house set. "I've made so many films about Italians!" Even so, the themes rising from the genre settings of CAPE FEAR are reminiscent of Scorsese's past works: the characters (though not Italian) speak of similar moral dilemmas, and face recognizable tests of strength and vision. While they live outside of a concrete jungle, they definitely inhabit a Scorsese universe. "He tries to always do something different," says producer Barbara de Fina, Scorsese's wife of six years. "But the way it's evolving, it's getting very personal; I see a lot of him in the characters. I don't think he could live with making a movie that wasn't personal." Scorsese's films (especially MEAN STREETS, TAXI DRIVER, RAGING BULL and AFTER HOURS) typically focus on the dangers and anxieties of his characters' private lives. "I don't know what you call what I do," Scorsese says, when asked to describe his style of filmmaking. "To me, it's like a hyper-reality of some sort. How can it blend with this material? Of course, maybe you can revise the genre, or I should say, make a revisionist version that does not deny an audience the thrills of the genre — that's the trick." But the most enticing aspect of this remake of CAPE FEAR is implicit in its title. It is more about an emotional state (for both its characters and its audience) than just about any Scorsese picture yet. "It's about fear a great deal," Scorsese says. "Fear and anxiety and edginess. Towards the last half, the family at any second threatens to come apart completely. So that's kind of nice. Tension is so funny. When all the doors are closed and a guy has no choices, it's kind of fun to see all the different options being closed away. It's almost like some sort of wry, moral game that's being played."

De Niro showed a very strong interest in a remake of CAPE FEAR when he was contacted by Spielberg, whose Amblin Entertainment is co-producing the $34 million film with Capa Productions. Together they persuaded Scorsese last summer to direct Wesley Strick's script, which had already undergone a stage of development with Stephen Frears and Donald Westlake (the team responsible for THE GRIFTERS) before Scorsese agreed to the project. The '62 CAPE FEAR, shot in black and white, has endured for its depiction of one of the screen's strongest portrayals of a psychopath. Yet the film, which comes down on the side of vigilante justice, is a little simplistic and out-of-step with contemporary thinking, a problem that did not escape Strick. "I didn't like the vigilante implications of the story," says Strick, whose attempts to persuade the producers that he was the wrong writer for the project got him hired instead. "I certainly didn't want to promote the idea that guns ultimately solve problems – you know, 'There comes a point when a man's gotta be a man and shoot this guy down.' If you could tell the story with another kind of sensibility, it would just be more ironic and full of dread, more a fable of the thin veneer of civilization. This perfectly decent guy has committed an ethical transgression, but in a sense it was the decent thing to do. But now of course this is all coming back to haunt him, and it escalates into this really grotesque life-and-death confrontation."

Even Scorsese's most commercially intended efforts (THE COLOR OF MONEY, ALICE DOESN'T LIVE HERE ANYMORE (point to his fascination with characters trying to break out from the confines of an environment that defines and often stifles them. The Bowdens – on the surface calm and secure – are in a sense trapped in the tranquil community of New Essex, hiding within their deceptively safe home from the evil lurking outside. Oscar-winning cinematographer Freddie Francis (GLORY) is using his experience as a director of thrillers for Hammer and Amicus Studios in England to help Scorsese capture the atmosphere of a "normal" house changing along with that of its "normal" inhabitants. One of Scorsese's goals is to paint a more realistic portrait of an American family, particularly a dysfunctional one in which tensions already exist, merely waiting for an outside force to arrive and knock a delicate situation completely out of whack. "There seemed to be an element in the script where the family was a very, very good old-fashioned American family; everybody's having a good time," says Scorsese. "That's very deceptive. Every family has its conflicts, and some are expressed in certain ways, others . . . well, others are never expressed. This is a family that normally I don't think would express it. "There are lots of undercurrents between a husband and wife, father and daughter, mother and daughter, mother and daughter against the father, father and daughter against the mother. And we started to get into all of that, and it became very alive for me. We weakened the family already, you see. The family was already weakened, like most families are." Although De Niro has portrayed a wide spectrum of personalities on screen, he is most acclaimed for his collaborations with Scorsese. This, their seventh film together, will no doubt draw comparisons to their earlier films, and the most obvious parallel between Max Cady and another De Niro/Scorsese character is to Travis Bickle, from TAXI DRIVER. But Cady does not stand apart from others, pretending to be unaffected by the horror and degradation that surrounds him, something on which Bickle prided himself. "There's no doubt De Niro and I are attracted to similar characters that we've dealt with before; they're similar – they're not the same. There're different angles in each one. It's almost like trying to find out how many more sides you can find to a character like Travis or Max or Jake LaMotta, or Jimmy Doyle." Another familiar Scorsese theme personified by Sam Bowden is that of the protagonist who questions and often rejects his own code of ethics and morality, and ultimately tests himself in a way that subverts preconditioned patterns of thought and behavior. Just as Henry Hill ends up betraying the very trust upon which he'd built his entire life in GOODFELLAS, and as Jesus questions — and for a brief moment refutes) his divinity in THE LAST TEMPTATION OF CHRIST, Sam Bowden is forced to question his belief in the strength of the law, and in the process re-examines the strengths of those who give the law a human face. Nick Nolte asserts that Sam is an example of the breed of lawyer who hides behind a mask of objectivity that is the law, which consequently protects them from the ugliness and horrors of the world — in effect reducing their capacity for empathy and courage. What Bowden is forced to confront is actually within himself: the understanding that beneath the trappings of society man is still a primitive. "I don't find Sam's reaction to violence that difficult," says Nolte. "It's not what we usually portray emotionally in movies as far as heroes are concerned, but it is heroic in a certain way; he recognizes every weakness. He's absolutely forced to. In fact he is covered with blood and is horrified by it, and is horrified to acknowledge the savagery to which he has descended. "He is not a perfect man; he's very flawed. It's very hard for Sam to accept powerlessness and not be a willful kind of person. But it's all part of the lawyer mask, too, to present this front of being an inviolable person that's totally capable, and not showing the humanness, the weaknesses. Lawyers must strive to be even more human rather then to dehumanize themselves. Most lawyers won't talk about that sort of thing because they won't admit they've got a mask. You go into a big public defender's office and they're deathly scared to discuss ethics, because they want it to look squeaky clean." When Jessica Lange was approached to play Leigh Bowden, her part didn't really exist. (Although Leigh is by definition a housewife, she works as a freelance graphic artist.) Her character was originally defined by her reactions to the tensions generated by Cady's presence. "It wasn't much more than just The Wife," she recalls. "It was the most dispensable of the characters, not inherently unique or fascinating. And I don't think they really planned on addressing the character until they knew who was going to play it. "But I've always been such an admirer of Marty, and when I met with him, I began to realize that he was wide open to doing something with this character. We had a lot of ideas to try and make Leigh a little more unusual and complex, and Marty's great about that — he loves to mix things up as much as the plot can stand." With Scorsese and Strick, Lange has helped Leigh develop a sardonic sense of humor, as well as a streak of discontentment which fuels both her mistrust of her husband and her reluctant fascination with Cady's motives. Her relationship with the daughter, Danny, is also more awkward, making her partly responsible for the young girl's unsteadiness in the face of danger. "When you cast a part with the right person," says Scorsese, "somebody with intelligence and amazing creativity, more than half your job is done. Even if things are lost as you go along in the editing room, the work has been put into the character by her, just by her presence. Even if lines are lost, the looks are right and that's very hard to get."

On the set, much of Scorsese's energy is given to pacing, making wisecracks and discussing film and music. But being on location first thing Saturday morning begins to test even his patience. "Six-thirty in the morning, we've got all this equipment, and for what? Two people are walking out of a building. It's hard. I'm complaining, but what would I be doing? I don't do anything on the weekends anyway. I'd be watching a movie or reading or editing a movie, so I might as well shoot." The past couple of days have been very physical, with actors wallowing in blood as two characters met their doom. A constant stream of jets taking off and landing at the airport near the Bowden house has not only disrupted shooting, but has taken on a more ominous aura as the developing Gulf War news plays on the TV downstairs. Airliners have been an unwelcome intrusion, and the filmmakers have stayed in contact with the control tower in the event heavy traffic is feared. (Once rush hour is over, however, the roar of planes passing overhead is replaced by the steady drone of cicadas which, curiously, sounds louder.) On this Saturday, the production has shifted to Miami, for exteriors and interiors at the courthouse. Scorsese is looking forward to working with Gregory Peck and Martin Balsam — alumni from the original CAPE FEAR who will be making cameo appearances (as will Robert Mitchum): "I wanted to get as many people as possible from the original but we ran out of characters." On the set Scorsese's assistant, Joe Reidy, carries much of the responsibility — and does much of the yelling — to organize the mechanics of a shot, and once the camera's tracks are laid down he runs through a rehearsal before Scorsese even looks at the set-up on his video assist monitor. The director luxuriates in the widescreen composition, which captures the faintly portentous columns outside the courthouse, as Sam confers with his boss (played by Fred Dalton Thompson). Only in retrospect does one realize that none of Scorsese's films has been in widescreen; although he's created powerful images in his past films, their visceral strength and the intimacy of his compositions are not usually associated with panoramic vistas. ("Oh, yeah, a love story in a tenement in 65mm," he muses). The early intimate features by the proponents of the French New Wave – Truffaut, Godard, Chabrol, Rivette — were in widescreen, despite the use of hand-held cameras and rapid editing, and those are characteristic of some of the dynamics Scorsese seeks to capture on screen with CAPE FEAR.

"I tried to create a psychopath who is more interesting, who has a real sense about himself being on a religious quest," says Strick. "The vengeance that he's seeking is pure and just and cleansing. Not only for him but for Sam, too. I mean he absolutely believes that he's Sam's doom but he's also Sam's redemption. And I think Marty really sees Cady's point of view. He can let his vision extend to the most black part of his characters." Since CAPE FEAR is being filmed more or less in continuity, the picture's rowing climax has been left for last. It is the most logistically complex sequence of the entire picture, culminating in the final confrontation between Cady and the Bowden Emily, on board a houseboat on the isolated waters near Cape Fear. This sequence, which will last approximately 15 minutes on screen, should take about two weeks to film. Since the setting is at night on the water in a torrential storm, the time required to capture this scene on film – expediently and with the greatest possible safety for the actors — necessitated the construction of a 90-foot-long water tank. A couple of weeks prior to shooting, the structure resembles a half-finished, overgrown garden shed covering an empty swimming pool; it will, however, fill in for the river and shoreline, and hold either of two full-size mock-ups of the Bowden houseboat. (After filming, the structure will operate as a sound stage for future Florida productions.) "It was hard making that commitment to build something so big," sighed De Fina. "In the overview, I guess the amount of money we spent to build the tank we'll save by not having to worry about things like weather and tides and alligators." The storyboard prepared for the finale shows in detail the quick cuts and mind-boggling camera moves Scorsese will utilize to make the final turns of the screw before exploding in fury. "He's using very dramatic camera moves, deliberately making them more visible to the eye," says Thelma Schoonmaker, the editor will whom Scorsese has worked almost exclusively in recent years. "Marty says, 'I like to grab them by the back of the neck and say, 'Look at this! and Look at that!' And so he's doing a lot more of that kind of stuff here, and he can get away with it more because it is a thriller. I can feel it in the dailies already — I feel a tremendous amount of tension." The challenge for Scorsese, however, is that all of his skill and technique is for the first time being put into the service of a linear plot. Most of his past films have been character studies, wherein the progression of plot was expressed almost offhandedly through behavior, location or even lighting. Here, each plot point meant to tighten the screws must be made perfectly clear, and a visual style must not detract from the plot if the tension is to be kept up. "It's handling the exposition that is most challenging and disturbing to me at the same time," he says. "And a lot of times I feel my strengths are elsewhere. I certainly don't throw it away; I try to express it in camera moves, turns, close-ups, tracking shots, whatever. There is a sequence of locking up the house that's kind of funny, kind of nice. A lot of wild compositions and stuff. Camera at weird, disorienting angles, to keep it edgy. "In certain cases we have built sets, but I would have liked to have built the house, because so much of the film takes place in the house. And all of my shots were envisioned as if there were no walls, no ceiling, no floor, pull-out roofs, and we've had to alter certain things because of that." "You can tell just the way he works on the set," suggest De Fina, "that there are the days that he's doing the stuff that he's certainly very confident with, and then there are the days he's making sure he captured all the pieces of information, and it's very hard for him. I think he doesn't realize that it really is sort of familiar: it's just different. Because in the final analysis I think this is a character study; there just happens to be more detail." Some of the techniques being considered or tested on this production are, of course, subject to change or further revision. Schoonmaker speaks of how, because of the wealth in the performances, a split-screen might be used on occasion to keep all the actors visible in a scene. Francis also is considering using special filters (as he had done on the Jack Clayton film THE INNOCENTS) that selectively shade those areas of the wide-screen frame that are not the center of interest, to make them murkier, more mysterious. Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of experimentation may be in the music, a key element in most films, and particularly potent in thrillers. "The music from PSYCHO keeps coming to mind the past few days," admits Scorsese. "Scenes remind me of that Bernard Herrmann music in the background, very soft. You can feel Ulat; it goes through my head constantly." Herrmann (whose last score before his death in 1975 was for Scorsese's TAXI DRIVER) composed one of his more chilling pieces for the original CAPE FEAR, and his compositions will be used again in this version, with the original score orchestrated and re-cued by Elmer Bernstein, whose credits include the Scorsese-produced THE GRIFTERS. As he nears the end of shooting and prepares for editing this journey into fear, Scorsese pondered the ephemeral, elusive quality of film, and of the dreams and nightmares which CAPE FEAR may come to represent. "Movies to me are a real dream state, they're much more real to me than people on the stage. The people on stage I know are really there. There's only a few people I've seen over the years in the theater that make you forget that they're real up there. "Dreams," he asserts, "are more real to me." And so are nightmares.

|

copyright 1991-2009 by David Morgan

All rights reserved.

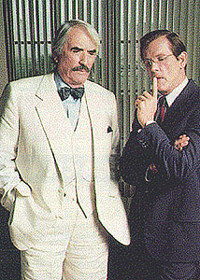

There

is a hush later when Peck makes his entrance in the corridors surrounding

the courtroom. It is only fitting that he is wearing a white suit, a reminder

of his performance as Atticus Finch in TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD, except here

he serves as the attorney for Max Cady, arguing at a hearing before the judge

played by Balsam. Peck is followed by De Niro, who plays his scene hobbling

on crutches, his face battered and bandaged, having been attacked by goons

hired by Sam. Unfortunately, the fight which should have sent Cady running

away with his tail between his legs has done the opposite: set Sam up for

a humiliating fall.

There

is a hush later when Peck makes his entrance in the corridors surrounding

the courtroom. It is only fitting that he is wearing a white suit, a reminder

of his performance as Atticus Finch in TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD, except here

he serves as the attorney for Max Cady, arguing at a hearing before the judge

played by Balsam. Peck is followed by De Niro, who plays his scene hobbling

on crutches, his face battered and bandaged, having been attacked by goons

hired by Sam. Unfortunately, the fight which should have sent Cady running

away with his tail between his legs has done the opposite: set Sam up for

a humiliating fall.