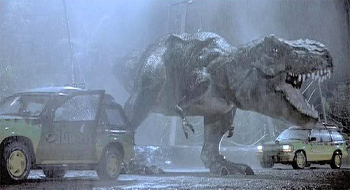

SPECIAL EFFECTS // "JURASSIC PARK" (1993) |

Suspending Disbelief |  |

|

"When you get into a level of imagery that's never seemed so realistic before," says Dennis Muren, the effects supervisor of TERMINATOR 2, "it transcends everything; and JURASSIC PARK is going to do that for dinosaurs. Everyone's seen hundreds of dinosaur movies, but actually, they've never seen a dinosaur before." Muren's point is that audiences were always aware that what they were watching was carefully crafted special effects. The goal of Muren and his fellow special effects artists is to help the audience forget that they are watching a movie — to convince them that dinosaurs do exist. And in JURASSIC PARK, they have their greatest opportunity yet to showcase the capabilities of computer generated [or 'CG'] images, to recreate animals that disappeared from the face of the earth 65 million years ago. In the past, dinosaurs may have been brought to life on screen by magnifying lizards, so as to appear a hundred feet long. Puppets or men in rubber suits might also be employed. But the first successful means was stop-motion animation. By constructing miniature dinosaurs and filming them one frame at a time, carefully adjusting their position little by little, animators could create the illusion of fluid motion. The best animators to work in this field included Ray Harryhausen (THE SEVENTH VOYAGE OF SINBAD, JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS), Willis O'Brien (KING KONG, THE LOST WORLD) and Jim Danforth (WHEN DINOSAURS RULED THE EARTH). "Go-motion," a variation of this technique developed at George Lucas' Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), used tiny computer-driven motors to control the movements of these miniature models. This was used in DRAGONSLAYER with spectacular results. Mark Dippe, Co-Visual Effects Supervisor of JURASSIC PARK who initiated the first experiments in CG dinosaurs at ILM, notes that the limitations of working with miniature models are eliminated, when the creature is designed and developed within computer space. "The physical rigging for a stop-motion creature actually limits the performance of your creature. If you have wires and cables and rods and other connecting elements supporting your model, you can't move it freely. The digital creature, however, is free to move about in any dimension you want, on any axis, or any joint. To highlight this point, in JURASSIC PARK the credit for CG dinosaurs reads "Full-Motion Dinosaurs." "We began to push for certain scenes to be done with computer animation," continued Dippe, "and once our first tests were to a point where we felt confident, we showed the film to Steven [Spielberg] and it blew him away. I think it's fair to say that once the freedom of computer animation was known, new scenes were added to the movie to take advantage of it. There are now some very intense scenes involving animals struggling and chasing that weren't in the original storyboards, because they couldn't imagine how it could be achieved."

CG images for JURASSIC PARK were actually accomplished in two ways. One method was to copy with a laser small models built by the film's conceptual artist, as a blueprint. Their exact proportions would therefore be registered onto a computer.

Once fully-animated skeletons were finished, ILM — using software it had developed for TERMINATOR 2 — would apply layers of coloring, to represent skin and muscles, by painting colors and textures onto these computer creatures, which would bend and turn with the creature's skeleton. These layers could also be easily changed and manipulated. In addition to changing colors and lighting, reflections and shadows could be imprinted; wetness from rain could be added. Dirt could stain the dinosaur's skin. Even bird droppings were added to one dinosaur surrounded by flocks of birds. These elements would then be digitally joined with background plates shot on location in Hawaii, where an actor's movement was choreographed to match with the expected movements of the dinosaurs. The total time to create and join elements of one shot could be from 6 to 10 weeks.

Another way of producing computer generated animation was to incorporate the work of a trained model animator. Many shots were created in conjunction with Phil Tippett, an animator whose credits include the STAR WARS and ROBOCOP films, DRAGONSLAYER and WILLOW. A self-professed "super amateur paleontologist," Tippet was actually going to create go-motion miniatures for JURASSIC PARK, but once Spielberg decided to utilize CG images, Tippet worked with ILM to generate animation using his own staff of animators. Working with a specially-designed apparatus called a "Dinosaur Input Device" (or DID), an animator would manipulate a model with special electrical encoding devices built into the joints, so that changes of position could be recorded on a computer. That data could then be fed into ILM's computers to create a skeletal animation, which could then be edited and altered. Muren now claims that the go-motion animation process is "obsolete," because CG technology allows incredible freedom not only in the creation of a subject — in this case a dinosaur — but in the planning and staging of camera angles and camera movement as well. Because the action of a model figure is no longer limited, camera movement is no longer restricted; computers can graft one image onto another without any problems of registration, focus or matching positions or speed within a frame.

Before JURASSIC PARK's dinosaurs could be brought to life, however, they had to be designed. Working with several paleontologists who were hired as consultants, the films' special effects artists took great care to stay true to the existing knowledge of dinosaurs, based on fossil remains and scientifically accepted notions about their appearance and habits. There is still a great deal of information not known about dinosaurs, however, leaving important questions for the filmmakers to answer. How, for example, might an animal weighing 6 tons and walking on two legs run fast enough to catch a jeep? Muren suggests that the revolution in effects technology may in fact make the job of an animator more difficult, in terms of an audience's suspension of disbelief: "When you don't have any matte lines anymore, and you don't have any lighting mismatches, or any sense of a rubber animal, or of a shadow looking wrong, then all you've got to look at is the performance, and that's where all the focus goes." Because there are no references for an animator to go by in deciding how a dinosaur should look and move, the animator needs to study the movements of many animals, and intuitively decide which behavior would be appropriate for a particular dramatic situation. "You have to make a collage of ideas," says Muren. "You think they would behave at one point like a lion behaves when it's hovering over its prey, but it's going to be moving with the speed of an elephant." Animators from ILM toured a nearby zoo and safari park to study animals such as lions, elephants, alligators and giraffes up close, to watch their behavior as well as their muscular movements. They also took classes in body movement with a noted pantomime artist, who helped them develop a way of connecting with an animal's feelings and attitudes, so that they could act out the character's behavior while drawing it. Still, the freedom that computer generated graphics gave the filmmakers was not appropriate for every filming condition. Ideally, the best place to have your dinosaurs would be on the same set as the actors — not only to help their performances, but to get as realistic an image as possible. Just as CG would be the best process to capture a herd of dinosaurs running down a hill, a close-up of a dinosaur would best be captured by constructing a life-size dinosaur head, with as much detail as possible. Stan Winston's previous credits include ALIENS, PREDATOR and TERMINATOR 2, in which he has proven himself to be a master of creating believable mechanical creatures. Having initially designed the look of the film's dinosaurs, Winston's crew devised full-scale props, such as a huge claw or tail, and even built one full-size Tyrannosaurus Rex: a hydraulically-driven model weighing 4-and-one-half tons and measuring 40 feet long. (Winston also created suits of the smaller dinosaurs that could be worn by actors, in scenes where they interacted closely with the film's human stars.) "Really what it gets down to, the nuts ands bolts of it all, the outside look, it becomes an artistic call, it becomes instinct, your vision based on all the material that's out there. Once you have done your studies and you know what a T-Rex is and what different paleontologists have said about its lifestyle and size and structure, and you start putting that down in the form of a drawing, you have to look at elements that there is no real information on — what was their skin texture, what was their coloration, what did they look like? In the final analysis, what's right is what looks right. It's not what is right, because nobody knows. This T-Rex is our T-Rex, what we felt looked the most real, the most believable, the most organic, the most dramatic. So when I look at it, I can say, 'That's neat! That's bitchin'!' It's right because I like it." Did working so closely with these lifelike beasts stir some primal fear within Winston? "No. I never had nightmares. I've had this primal instinctive silliness where I go, "Oooh, that's neat!' or "Oooh, that's so coool, that's just so neat!' And that's what it's all about, when it excites me with its reality, its beauty and its artistic finesse, and its historic finesse, and I can look at these and go These are the neatest dinosaurs I have ever seen in my life.' Why? Because I think there are. And it doesn't mean that somebody else will. There going to be some dinosaur person out there who's going to look at these dinosaurs and go, 'That's not right,' They wouldn't look like that.' It's impossible to please every connoisseur of dinosaurs." Prior to shooting, sequences had been drawn out, shot by shot, by a storyboard artist. Tippett and his crew then created a videotape version of the storyboards called an "Animatic," which served as a guide so that camera angles, movement and cutting could be experimented with before getting onto the sound stage. Tippett created animated shots of the dinosaurs, using dolls to stand in for the human characters. But although shots might be choreographed on paper, they could not be tested in advance of principal photography to see how well the live-action dinosaurs performed. Winston: "There's a strange thing about the movie business which is exciting and also very scary, and thank goodness there are creative and imaginative people that will take big risks: the movie is the prototype. Now we know how to do it. Now we can go back and do it right. You don't have time or budget to whatever to build a prototype machine and then say, Okay, now let's clean it up and make it work.' You start designing and building and you correct as you can on your way, there is no prototype. We're shooting the prototype. We're shooting the test. And the magic of the filmmaker, like Spielberg, is being on and set and being able to creatively on the spot have whatever he's got that you've been developing for a year and a half, two years, and say, Well, it does this great, I can do that; it does this even greater, this is better than I thought it could do, I can really use that; it doesn't do this right, I wanted it to do this and it's not doing it,' and get creative on the spot and make it work a different way." Once the mechanical dinosaurs were brought onto the set and put through their paces, how they functioned affected how a particular shot was staged — and then, the storyboards might have to be altered so that other connecting shots would match. The most dramatic change was with the velociraptors, or 'raptors,' who hunted in packs and were the main antagonists in Michael Crichton's book. "The initial notion was to make the raptors somewhat bird-like," said Tippett, "but once Steven started working on the set with the full-scale props, we decided that they worked better when they were moving slowly or more stealthily. So the idea was changed from the quick, more bird-like effect to something eerie and stalking, more slowed-down. "One of the notions that we were adamant about was Spielberg's request that the dinosaurs be animals, and not monsters — certainly not Hollywood monsters," said Tippett. "One of the ways to accomplish that was to stage shots which would go on for some time, like in a wildlife documentary, so that you had time to examine the characters and see what they were doing, rather than creating a montage that is compiled, cut to cut to cut, as most special effects films are done, where a threat may be implied by shadows or blurred, quickly-moving figures."

Tippett helped choreograph these scenes and was on the set with Muren to work with the director of photography and Winston's physical effects crew to coordinate the animals' movements, even for shots where they were required to do little. "For some of the raptor sequences," Tippett said, "I tried to develop some holes in the action where the dinosaurs didn't do anything; the animals just stayed there and were quiet and still, but the scenes would intone a certain sense of threat, a sense that something sinister was going on." The breakthrough in this film in terms of compositing images, however, is that, using computer motion control software, ILM's camera operators were able to duplicate whatever hand-held camera moves were done on location. The dinosaur elements were then capable of being inserted seamlessly into the action, even in a busy shot with crowds of people running around, with the focus changing from close-ups to wide angles. JURASSIC PARK has broken the accepted rules of special effects photography by expanding upon traditional methods of character animation. But because many artists are inexperienced with computer generated imagery, the new technology's unfamiliarity and lack of limitations may seem intimidating. "There's definitely a Renaissance in visual effects right now," says Muren, "and it could go in any number of directions. We have more tools in filmmaking now, and with so many options it's very dangerous if you don't have a solid grasp of the technology." Which, in an ironic way, is one of the themes of JURASSIC PARK — learning to control a new science.

Muren, Tippet, Winston and John Lantieri won the Academy Award for JURASSIC PARK's effects, and returned for production of the sequel, THE LOST WORLD. Muren also supervised ILM's effects for the STAR WARS Prequels, A.I., and WAR OF THE WORLDS. Tippet created the giant bug effects for Paul Verhoeven's STARSHIP TROOPERS, and directed that film's sequel, STARSHIP TROOPERS 2: HERO OF THE FEDERATION. He also handled effects for DRAGONHEART, THE HAUNTING and THE SPIDERWICK CHRONICLES. Dippe was SFX supervisor, producer or "guru" on RISING SUN, THE FLINTSTONES, TWO TICKETS TO PARADISE and SCOOBY DOO! THE MYSTERY BEGINS. He also directed SPAWN. Winston contributed to INTERVIEW WITH THE VAMPIRE, THE GHOST AND THE DARKNESA, TERMINATOR 3: RISE OF THE MACHINES, CONSTANTINE and IRON MAN. He passed away in 2008. |

copyright 1993, 1997, 2009 by David Morgan

All rights reserved.

For the artists whose experience has been in lower-tech effects, the computer may have seemed a bit daunting. Muren: "It takes years to learn this, just to learn the computer part of it. I took a year off after we did THE ABYSS and bought a computer and stayed at home and learned it, because I couldn't get the time at work to do it, and I had to kind of learn it the way I learned photography as a kid: you do it at your own pace and make thousands of mistakes till you know how the thing works. But I've still only scratched the surface of it."

For the artists whose experience has been in lower-tech effects, the computer may have seemed a bit daunting. Muren: "It takes years to learn this, just to learn the computer part of it. I took a year off after we did THE ABYSS and bought a computer and stayed at home and learned it, because I couldn't get the time at work to do it, and I had to kind of learn it the way I learned photography as a kid: you do it at your own pace and make thousands of mistakes till you know how the thing works. But I've still only scratched the surface of it."

Using that information as a guide, animators could click a mouse to move a creature's joints just as a model animator would manipulate a model's joints, except all information was recorded in "computer space" instead of on film, as a moving dinosaur skeleton. Most importantly, this work — once stored — could be repeated, reviewed and corrected easily, whereas with model animation any mistakes would force an entire shot to be refilmed.

Using that information as a guide, animators could click a mouse to move a creature's joints just as a model animator would manipulate a model's joints, except all information was recorded in "computer space" instead of on film, as a moving dinosaur skeleton. Most importantly, this work — once stored — could be repeated, reviewed and corrected easily, whereas with model animation any mistakes would force an entire shot to be refilmed.

In that regard, the ability to see the creatures think as they hunt, to see motives in their behavior, was the ultimate goal of the effects artists, so that audiences might believe that these dinosaurs are as dangerous as a wild animal on the loose.

In that regard, the ability to see the creatures think as they hunt, to see motives in their behavior, was the ultimate goal of the effects artists, so that audiences might believe that these dinosaurs are as dangerous as a wild animal on the loose.