PRODUCTION DESIGNERS // "THE AGE OF INNOCENCE" (1992) |

Inside Edith Wharton's World |  |

|

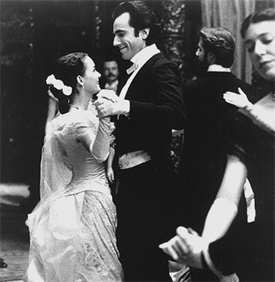

"I've worked with first-time directors," says art historian and production designer Robin Standefer, "and I find that I do a lot of the same work that I see Scorsese do on his films, in terms of designing." For a hands-on director like Martin Scorsese, who submerses himself into every aspect of filmmaking, Standefer was a resource who could be counted on to provide invaluable information from her particular field – in this case, art history, without which THE AGE OF INNOCENCE could not exist. Standefer, whose first studies were art history, architecture and theatrical set design, began her motion picture career with Scorsese on "Life Lessons," his contribution to the 1989 anthology feature NEW YORK STORIES. "Scorsese had asked me to come on board as a fine art consultant and find the painter that Nick Nolte was representing, and help with decorating the interiors of Nolte's studio." Standefer paired the director with Chuck Connelley, a Lower East Side painter whose canvases adorned the film. Standefer then worked as a researcher and later a set decorator on GOODFELLAS, a period picture that perfectly captured the awful tackiness of 1970s pop culture in Queens, New York. She has also earned credits as a production designer, working on actor John Turturro's debut film as a director, MAC, and two films by writer-director Michael Tolkin, THE RAPTURE and THE NEW AGE. But it was THE AGE OF INNOCENCE which marked Standefer's most labor-intensive project. Because Wharton's story is very much an anthropological study of New York society in the late 19th Century, the success of the picture would be contingent upon the choice and use of locations, including the building of sets, to recreate New York of that era – a difficult feat to accomplish considering the extent of demolition and revamping of historic sites over the years, as well as the irreversibly modern landscape sprung up in Manhattan. [Often, period pictures set in New York, such as THE BOSTONIANS, RAGTIME, SHINING THROUGH and THE PUBLIC EYE, are filmed elsewhere for reasons of budget, time, or simply a lack of locations suitable for use.] The film taking place in Manhattan, Newport, and finally in Paris, required 65 different interior and exterior sets, almost all of which were achieved by using existing locations. The Governor's Office for Motion Picture & TV Development, which assists filmmakers using New York State as a movie set, shot thousands of photos of mansions that might serve as possible sites for the film. And in some instances, the real-life society figures who inspired Wharton's characters – and who were revealed by her biographer – were researched, using period photos or paintings to establish their appearance and lifestyle. "I put together a huge library," Standefer said. "I read period etiquette books. I went to food archives to study what kinds of meals were prepared and how they were served; [for example,] every meal served in the film had its own particular table setting." All of her findings were laid out as keys which could be referred to throughout location scouting and filming, to make sure that each element of the film was accurate to the time period and place. Still, when reading Wharton's text (and other contemporaneous sources) within a modern context, one must be aware of the relative terms used to describe the opulence of the Gilded Age. "They always referred to their summer residences in Newport as 'cottages,' and my idea of a cottage is not something with 35 rooms, and 50 servants and footmen and landscapers!" Unfortunately, none of the places specifically mentioned in Wharton's book as settings for her drama still exist, or have maintained their appearance after one hundred and twenty years. Approximations were located by the filmmakers, however, throughout the New York area. A train station scene was shot in Hoboken, New Jersey, and – after reviewing over 900 possible sites nationwide – a music hall in Philadelphia substituted for New York's Academy of Music [which had been demolished long ago]. Only one major set was built, for an ornate ball room sequence at the Beaufort residence that required a great deal of room to accommodate very intricate camera moves.

Standefer's knowledge of art trends of that period was crucial in helping establish – visually and dramatically – the differences among the families appearing in the film. "The trends in art were really a mirror to the transitions – social and political – at that time; what they reflected in terms of power and prestige, and how interior decorating subsequently affected painting and architecture." In addition to being used as guides to help design sets, paintings also served as set decorations themselves, illuminating the heritage and wealth of the film's characters, thereby revealing the same social and class differences that Wharton's book captured and satirized.

"And then we go into Madame Olenska's house, and it's much more Bohemian; her books are in different languages. Newland [Daniel Day Lewis' character] is wild about that! She has Impressionistic artwork, which was also considered unorthodox. The house is also much barer, containing many Oriental objects, Chinese and Japanese rather than Middle Eastern. Newland is intrigued by all this unfamiliar stuff, but he's also frightened by it." To add to the headaches of shooting, production designer Dante Ferretti decorated his sets with irreplaceable period furnishings – Schumacher fabrics, Tiffany china, furniture, silverware, books – making the images more splendid, even if these articles couldn't actually be seen by Scorsese's often-moving camera. Insurance was astronomical in the event a crew member knocked over the Baccarat crystal. Still, aside from the audience's pleasure at the visual extravagance, the authenticity did serve to support the actors, and in fact most of the crew could believe that they, too, were actually transported to an earlier, quieter era. The filmmakers' biggest break in terms of shooting space was the discovery of Troy, New York, long ago a home of affluent industrialists and state politicians from nearby Albany (as well as of discredited capitalists intent on starting anew after fleeing bankruptcy in New York City). Troy possessed the architecture necessary for filming exteriors representing 19th Century Manhattan's streetscapes, brownstones and mansions – buildings the nouveau riche of Troy had tried to emulate. There was even a row of townhouses that had been purposefully built to imitate Washington Square's design. "During the Depression so many cities like this had become completely poor, declined and deteriorated," said Standefer. "But the thing was, nobody ever built Troy back with modern housing, it was lost in time. Sort of like when a man dies without a will and nobody gets the house after he dies so it just sits? Troy just sat." Standefer spent almost a year in pre-production just doing research

and location work, before working with Ferretti as an assistant production

designer during filming. (Her credit reads "Visual Research Consultant.")

After shooting, she edited For Standefer, perhaps the most amazing discovery in her research

was that the interpretations of the styles, customs and etiquette of New

York's upper classes varied so greatly among historians, biographers and

art experts consulted for the film. For example, what was the accepted protocol

for entertaining guests for lunches or dinners, and how did that differ at

each stratum of society?

"I could find as much information to support a subject as to not

support it. I had five historians totally disagree about Wharton

and the way things happened then, even architectural details. And I'm saying,

'Wait, isn't there a factual basis for this?' No, it's very subjective!

It's terrifying, because you have a film, something that's going to be very

public, and here's a man like Scorsese depending on you to be right. And

there's very little empirical 'right' in history anyway."

Postscript:

Following her work on AGE OF INNOCENCE, Standefer served as production

designer for Julian Schnabel's BASQUIAT, PRACTICAL MAGIC and ZOOLANDER.

For Related Articles on THE AGE OF INNOCENCE by David Morgan: Interview With Producer Barbara De Fina (for Hollywood Reporter, 1992) Interview With Location Manager Patricia Anne Doherty (for Hollywood Reporter, 1992) | |||||||||

copyright 1992, 2009 by David Morgan

All rights reserved.

"These people lived vicariously through these paintings," said Standefer. "They were the cinema and TV of that era – and in a very specific way, because 99% of the paintings people collected were genre paintings: like Meissonier, who painted narrative scenes, including depictions of Napoleon; Troyon, a painter of livestock, such as cows, sheep, deer; Orientalists like

Gerome were common. We had to divide painters by family – everything became a representation of each family and how we saw them as a metaphor. Like the Bouguereau ("The Return of Spring," right), considered scandalous, that's hanging in Beaufort's hall.

"These people lived vicariously through these paintings," said Standefer. "They were the cinema and TV of that era – and in a very specific way, because 99% of the paintings people collected were genre paintings: like Meissonier, who painted narrative scenes, including depictions of Napoleon; Troyon, a painter of livestock, such as cows, sheep, deer; Orientalists like

Gerome were common. We had to divide painters by family – everything became a representation of each family and how we saw them as a metaphor. Like the Bouguereau ("The Return of Spring," right), considered scandalous, that's hanging in Beaufort's hall.