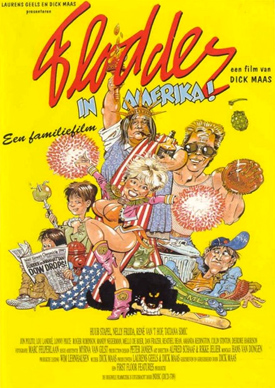

PRODUCERS // "FLODDER TAKES MANHATTAN" (1992) |

FLODDER TAKES MANHATTAN

|  |

|

During the winter of 1991-92, when contract negotiations between New York's film labor unions and film producers stalled, the major Hollywood studios engaged in a de facto embargo of shooting feature films in the City until such time as the contracts were settled. The decline was precipitous: the number of features spending all or part of their shooting schedule in New York in 1990 tumbled from the dozens to a handful. Unemployment among the city's film professionals rose, and many left town to chase the features then filming in Florida, Toronto, Chicago or elsewhere. The city lost out on millions of dollars in business and tax revenue, in addition to the free PR power of having New York appear on movie screens across the globe. Much of what filled the production void, however, were low-budget independent and foreign films, which discovered themselves in the enviable position of not having to compete with a $50 million star vehicle in finding qualified workers and obtaining access to attractive locations. One such film enterprise was the Dutch comedy FLODDER DOES MANHATTAN, whose producers spent about one-third of the picture's 11.6 million gilder (US$6 million) budget in Gotham. What the filmmakers wanted out of a New York shoot was the added-value of Manhattan locations to sell their comedy in the U.S.; what they neglected to factor in was that — despite a paucity of work from a business still recovering from the embargo — New Yorkers could still drive a hard bargain, bureaucracy may still rear its ugly head, and a hit film property from the Netherlands does not necessarily impress the Plaza Hotel if they can have Isabella Rosselini shooting outside their door instead. The following article features interviews with producer Lauren Geels, writer/director Dick Maas and actor Huub Stapel as they wrapped production here in April of 1992.  When asked why the Netherlands-based First Floor Features undertook a five-week location shoot in New York City for the sequel to their successful comedy FLODDER, producer Laurens Geels explained matter-of-factly, "The script read FLODDER DOES MANHATTAN. If you would have wanted to avoid shooting in New York you should have changed the screenplay, and that's not what we wanted to do." The first FLODDER film [about an eccentric, lower-than-lower-class family whose shocking behavior drives their well-heeled neighbors to blow up their house] has yet to be released in America, but the producers are hoping that its sequel's locale will generate interest in the U.S. market. To that end, this picture is being shot in two versions: Dutch and "American English." [UIP holds world distribution rights.] Gaining permission to shoot in New York in and of itself proved the most difficult aspect of coordinating an international production of a six million dollar film. Coming on the heels of Hollywood's film embargo [stemming from their stalled contract negotiations with the Teamsters], the myriad roadblocks put up by the NYC film community, labor representatives and property owners in front of FLODDER's producers seemed counterproductive, even ludicrous. The Screen Actors Guild, for example, originally demanded that all of the film's characters including the members of the Flodder family were to be played by American actors. "I've been amused by some of the union requirements, and sometimes a bit flabbergasted when some of their demands came to us," said Geels. "So it took basically quite a lot of paperwork: all sorts of letters, press clippings of the previous FLODDER movie, statements about the relationships between the main Dutch crew and the director and producer — in short, all sorts of bullshit. You also have to deal with Immigration for the visas for the Dutch members of the crew; immigration authorities take council from the unions, and the circle is complete — and the paper kept piling up higher and higher." The original cast of FLODDER was finally allowed to recreate their roles — this time, while exploring New York City as part of an exchange program. As Johnny Flodder demonstrates by driving through town in a Cadillac with leopard-spotted upholstery, the film is taking a European view of America and standing it on end . . .

At the same time, Stapel acknowledged that film crews in the Netherlands lacked many of the controls their American counterparts enjoyed, forcing many to work exceptionally long hours doing different jobs. If an actor wasn't on set and they needed someone to run a smoke machine, he'd be expected to run the smoke machine.

They did have to compete with other filmmakers for certain locations, too; weeks of on-again, off-again negotiations to shoot at the Plaza Hotel weren't concluded until Paul Mazursky's THE PICKLE had wrapped its scenes there. But with only half a day lost to rain, and a few minor shots cut to meet the schedule, the FLODDER crew wrapped in relatively high spirits, preparing for the completion of interior work in Holland. In fact, they seemed quite pleased to have survived shooting in what some filmmakers have acknowledged is a difficult but rewarding environment. "If you can shoot here," Maas said, waiting for a gerry-rigged limo to carry a camera platform through the streets, "you can shoot everywhere." Postscript: In the years since this interview, Manhattan has definitely made out better than the Flodders following their collision on film. Once contract talks were settled, new, much-heralded strategies for IATSE, NABET and the city's film commission to accommodate middle- and low-budget filmmakers have proven very effective. Consequently, the city has played host to an increasing number of both high profile and independent films. In 1996, more than 200 movies shot all or part of their scenes in the city or state; total revenues from film, television and commercial shoots were nearly $2.25 billion, and climbing. On the other hand, the Flodders have yet to make it to these shores. Although FLODDER DOES MANHATTAN (a.k.a. FLODDER 2 or FLODDER IN AMERIKA) and another sequel, FLODDER 3, apparently played in film markets in the U.S., neither the features nor a spin-off television series have been formally introduced to American audiences. |

copyright 1992, 1997, 2009 by David Morgan

All rights reserved.

"I think if you want to shoot here," reflects Maas, "it's impossible to prepare for everything, because there are so many rules and so many things that can come up in the shoot that are all surprises. But you can prepare yourself that there will be things that you can't foresee. That's how we went about it."

"I think if you want to shoot here," reflects Maas, "it's impossible to prepare for everything, because there are so many rules and so many things that can come up in the shoot that are all surprises. But you can prepare yourself that there will be things that you can't foresee. That's how we went about it."