THE TERRY GILLIAM FILES // "THE FISHER KING" (1991) |

The Millimeter InterviewBringing A Myth To Life In New York City |  |

|

"This is more like 'Alice in Wonderland' than anything else I've done." Coming from director Terry Gilliam, referring to his latest film THE FISHER KING, that statement portends a great deal. Gilliam's previous films, being exclusively his own untamable fantasies and Pythonesque adventures (including TIME BANDITS and BRAZIL), have earned him a notoriety for being without restraint, both in his imagery and in the lengths to which he will go to protect his work (and, in the case of his last film, THE ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHAUSEN, in the lengths to which he would go to outdo that reputation). The sensational designs and crafty stagings of his films have often overshadowed their human content, dealing with social responsibility, the misuse of political power, the force of myth and legends, and the mutability of love.

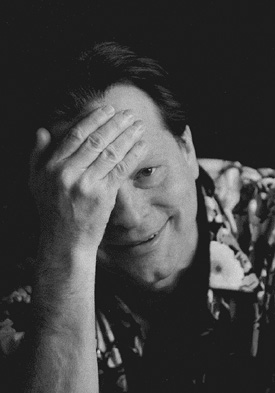

When this original script by Richard LaGravenese landed on his doorstep, the temptation to work as a director-for-hire on a major Hollywood film proved extremely powerful for Gilliam. For the producers, Debra Hill and Lynda Obst, it was an opportunity to work with an auteur and still maintain the discipline necessary for a $23 million production. Location shooting commenced in New York City this past summer (with all interior work to be completed at Columbia's Culver City backlot). By all accounts Gilliam's involvement has elevated the material from becoming what could have been perceived as a zany comedy into a darker, more human story of redemption; the troubled Parry, for example, experiences a pain and horror only hinted at in the screenplay's earlier development phase. With cinematographer Roger Pratt (with whom he shot BRAZIL), Gilliam has also made New York City appear more magical and hallucinatory than it already is. An intense, focused worker, Gilliam is nonetheless given to punctuate his speech with facetious jokes and giggles, which does much to raise the spirits of those trapped on a Downtown Manhattan location during a torrential rainstorm at 3 in the morning. Weather has been a major hindrance to the film (it poured three days during the first week of exterior shooting, and often enough later on), but the logistics have been more or less smooth, with the main obstacle being bothersome residents who don't appreciate their neighborhoods being filled with smoke.

Q: When we last spoke near the completion of shooting BARON MUNCHAUSEN, I asked what you had to look forward to. After contemplating suicide, you said you wanted to do something small, perhaps a film with a couple of people in a room, and that's it. And now you seem to have gotten your wish — although you haven't gotten to the room just yet. Gilliam: The room's always still in the future, yes. I really ran out of steam after MUNCHAUSEN. I think I had reached the point where I was ready to pack in filmmaking, I just was terrified of the whole process. Then my agent had sent THE FISHER KING along. He said, 'It's a really interesting bit of writing.' And after the first couple of pages I thought, Jesus this is terrific. It looked really simple. With all the attitudes, the characters, I just simply understood [the piece]. Like this medieval element, which is a strange thing because I think it could have been done totally mundane. Q: But you've opened up whatever subtext the writer himself may have been unaware of, but which seems totally truthful. Gilliam: At some point, I said that I thought that Richard didn't really appreciate or understand the totality of what he had written, of all his themes. But he did, on an instinctive, subconscious level. But I sort of pushed it. I've just pushed everything further. Q: Do you feel more secure in pushing it because it's not your own material? Like you're testing to see how far you can stretch it? Gilliam: No, actually I feel that I'm trying to be terribly responsible and loyal to the script. I said to Richard, `You know, all I can do now is fuck it up for you.' I don't want to do anything [he] wouldn't have wanted. And it's that kind of responsibility that is something I've never experienced. It's really weird; I don't like feeling that I could make a mess of somebody else's idea, and the first couple of weeks I was feeling maybe that's what I was doing. But we're getting on somehow. Q: How is the film meeting your expectations? Gilliam: My expectations were really just to have an easy time. And I failed at it. I really just wanted to do something very simple and I find that I can't. No matter how hard I try, to simplify it and do it direct, I elaborate it somewhere, and put the camera in a funny position, make it more of this or more of that. Q: Yet your elaborations are not taking the story away from what it really is? Gilliam: I hope not; I mean we'll find that out when I stick it all together. Q: Is it progressing in terms of the story that, as Jack becomes totally drawn into Parry's world, effectively becoming Parry, the film gets more and more skewed towards that point of view, where it doesn't show New York for what it is but as Parry himself sees it? Gilliam: That's what I've been trying from the beginning; the minute Jack steps out of the protective confines of his girlfriend's video store, it goes pretty weird very quickly. It's like in the Parsifal myth: as a boy he sees the grail, but when he gets to the grail castle, he doesn't do the right thing. There's a clarity of vision when you're young and then you lose it as you go on, and then you find it at the end hopefully; that's what making the film is like. It was really clear in my mind early on, and now that I'm into it I've lost it, so I'm stumbling through the forest blind at the moment. I'm doing a lot of it by instinct. It's true, that actually is what happens. I'm on auto-pilot right now. Q: And where are your instincts taking you? Gilliam: I don't know. We'll find out. I mean, what you do is you make a lot of decisions early on, and set a lot of things in motion, but what happens is then other things start affecting those things you started out with; your original plan is maybe not corrupted but confused by reality. And that's where we're at now. I go stumbling on blindly, and everybody says it's terrific, so I trust that it seems to be working. Q: You've worked before with a couple of members of the crew, but most are not experienced to working with you — a situation similar to that of MUNCHAUSEN. How are they (and you) getting used to it? And are you getting back into the drive of being able to shoot and work very quickly? Gilliam: Not yet. Not the first couple of weeks. It's going rather slowly. The team is coming together. It's a strange situation; to save money they ended up splitting the show between New York and L.A., which ends up that all of the team doesn't play all of the way through the film. I haven't seen what the results of that are going to be yet. And I don't like it because I've never done that before; I mean, you get a team and you go. The key people stay with it, but some of the lesser characters don't, and I'm worried to see about that; I don't know what's going to happen. What I wanted to do was fight my fantastical side, and I wanted people who were really well-grounded in New York. Like Mel Bourne, the designer: he's done Woody Allen films, he knows the nuts and bolts of New York, and that's why I wanted to work with someone who grounded the thing. Q: You're bringing out a lot of the medieval elements in New York: locations, the design of costumes, the character of the Red Knight, the castle serving as the millionaire's townhouse. Are you finding other elements of New York to put in? Gilliam: Not enough. I mean, they're there but we're not getting them on film. One of the most frustrating parts about this is that all my ideas of gargoyles and bits and pieces — it's all around, it's really easy [to find] in New York, there's "tons" of it — we lose it; we can't go to enough places and shoot enough things quickly. Q: Can a second unit do that while you're in L.A.? Gilliam: Uh, I'd want to do it myself. We'll see what happens. I mean the film's not over until it's over. I might be back with a tiny group and get a few goodies. We shot under the Manhattan Bridge, at the base of that bridge, and it's — well, it's actually not medieval-looking but it's sort of somewhere between Piranesi and Goya. So it certainly doesn't look like New York as we [usually] see it. At an entrance to the side of the bridge there's a great arch, which we use as Jack's passage into Parry's underworld. "Abandon all hope ye who enter here" is what it should have over it. We were getting very worried that some of the stuff that we were doing is a bit zany. And we keep trying to insert ugliness in it, and a certain brutality. At times the thing is like "Alice in Wonderland" and Dante and Virgil, it's all these things. There's a statue of Dante right outside my hotel. I can see him when I look out my window, in a little square right opposite Lincoln Center -- there stands Dante. Q: Is that an omen of some kind? Gilliam: Of course!

Q: Are you buffered from the studio by the producers? Gilliam: Yeah, they seem to be very supportive. I can't complain at all. I wish I could. But I can't. The important thing is that what they're seeing has impressed them and they like it, and that's the proof really. I mean, they were very nice at the beginning; I think they were very wary because of the MUNCHAUSEN debacle. Q: What did you learn from that? Gilliam: What, MUNCHAUSEN? Not to make BARON MUNCHAUSEN again. I learned not to work with a particular producer again. No specific things, there's no grand wisdom that's acquired by that. You've just got to be more careful. But on the other hand, if we had been more careful we wouldn't even have started the process, and there's a film there at the end of it, which is important. So you can't really say [the experience] was bad because if we had been more reasonable and careful and intelligent we wouldn't have gotten the thing off the ground. [On this picture] we've had certain problems in the first couple of weeks, it's just been really rough here; New York is impossible to work here, and we've, uh, slipped a bit. I began to think, 'Oh it's MUNCHAUSEN all over again.' Q: But you also have a much tighter budget this time, whereas MUNCHAUSEN started off with a blank check. Gilliam: No, it didn't. Starting off it was very carefully budgeted except totally unrealistically. The figures didn't match the reality of what we were doing. Q: Is this budget realistic even though it is tight? Gilliam: It better be. I don't know. I am slightly at a disadvantage having never worked here, I don't know what the money buys, but we've gone through it and it seems to be right. To be fair they, meaning Debra and Lynda, have not produced a film as ambitious as mine normally are. And I think it's hard for people; they don't seem to understand what it means when I say 'I want something like this. Even I don't; that's one of the reasons I ask for it. But a certain naivete makes you think you can do it and if you think you can do it, you have a go.

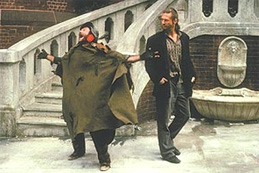

[The Manhattan Bridge location] again is a silly thing. We just stood here and said, 'Oh wouldn't that look nice as a background?' Well what is involved in making it a background is crazy, and for somebody to say 'You can't do that' would have saved us a lot of trouble; you could have done this scene just on a corner somewhere, but nobody said 'no,' so here we are. This little idea came up, I was watching rush hour traffic in Grand Central. There's a scene that took place at rush hour, and I thought, `Wouldn't it be great if all these people suddenly started waltzing?' Q: And people took you seriously. Gilliam: [shrugs] Nobody said no. Q: Are you expecting that one day somebody will come in and say 'No'? Because on MUNCHAUSEN, nobody told you 'No' until it was too late to do anything about it. Gilliam: Way out of control, yeah. The problem is the ideas seem to capture people, and everybody — not just me but everybody else — falls victim to these things. It's weird; ideas do this. Then you discover, it isn't just the waltzing; the pictures have got to look right. Then I want the lights in a certain way. It's all the details. That is the difference in shooting it with bad lighting and shooting it with good lighting; good lighting costs more money. What's interesting, when you work with good people, it doesn't really come out cheaper because their demands are greater. Really good people are full of ideas and they work to a higher standard. And you pay for it; it costs money. It doesn't come really cheap. Q: How is your working relationship with the department heads you've not worked with before? " Gilliam: The interesting thing with films is that the pattern is very quickly established. And because everybody knows that I'm involved in the design of everything on my films, when they walk in they know they're going to be involved with me. I stick my nose in much more than a lot of other directors might. Q: So you're not frightening them away? Gilliam: No, I don't think so. Good people, at least most of the ones I can think of, really like input. My problem is that I just have pretty clear ideas about a lot of things. And until I sort of get them I don't let up. But there's no way that I can credit myself for all this stuff. Like with the costumes for Jeff's character: I wanted Versacci clothes because I wanted the most expensive, sleekest stuff at the beginning. Jack's a guy who's really a product of America's materialism, all style and fashion — the best, slick, cool. But everything is monochromatic with him; there's blacks and greys, no color. And I like the idea of trashing his Versacci clothes when he becomes a bum, which is really silly when you're paying two thousand dollars for a suit and you're trashing it. Q: Jack's lost his job, he's lost his home, but he doesn't want to give up his clothes so he wears them into the ground. Gilliam: Uh-hmm. I also like the idea of seeing these very expensive clothes look like shit. It's been slightly harder on costumes for me because they're contemporary things and I don't have any great feeling [for them], and so Beatrix Pasztor and I would just spend a lot of time together, and Jeff is very full of ideas. Everyone's got ideas, that's what's nice about it, and I just become the guy who sort of guides it through and says 'I like that' and 'I don't like that.' Basically Jeff's costumes are Jeff, Beatrix and I sitting in a room for hours on end, all shifting around. Robin, the same thing: Parry had to have this medieval aspect, and what's nice is that it's all real modern stuff. With that cape and that poncho and hat, he really comes out of a Bruegel painting. And underneath it he's got this bit of gold lame, looks like some golden fleece or a bit of chain mail. And all that's been good fun, to try and assemble what is believable and yet has this total medieval quality to it. It's nice working like that. You know, I think a lot of directors just don't do any of that stuff. They just hire the costume people, the costume people say, 'Bum bum bum, this is how we're gonna do it,' the financing's all right and that's the end of it. I just think that takes the fun out of it. It's always like doing a painting. You just want to have all the parts the way you'd like them in a painting. I mean, on this one, I'm paying much less attention to background than I normally do because it doesn't seem to be what this film is about. Q: This isn't a case where there's always something going on very deep in the frame? Gilliam: No, I'm not doing that on this one, I'm just tired of looking back there any more. I don't want to lose the characters in that sort of deep photography; I want to keep them in the center. I hope I pull it off. Q: Are you finding that here, among the crew, you can be the team player you've been before, as opposed to being thrust into the position of "Director-God" as you were by the Italian crew of MUNCHAUSEN? Gilliam: Yeah, I'm very much a team player, but because people don't know me they don't say 'No' early enough; they don't say 'Wait, hold on a minute, are you serious about that?' or 'Have you considered maybe there's another way of doing it?' One of the problems here is that they seem to respect me too much. The people I'm working with like the films I've done, and they think I know what I'm doing. In England people are much better about saying, 'Well, why do you want that? Do you really need that? Hold on a minute, wait wait wait, let's talk this through.' Q: There are no Devil's Advocates in America? Gilliam: Not as many as there are in England. I think that's why I was lucky to have ended up in England, because they're less impressed. Here people really are excited about films. And they do love this thing about Terry wants something! so then everybody runs to make it happen. And they don't always think, 'Is that an intelligent thing he was asking for?' And that's the problem of getting older and making more films, too — 'The guy clearly knows what he's doing; we've seen these films, and are impressed with them.' The fact is, he doesn't know as clearly as they think he knows what he's doing. I think I've got to go back and do one in England where people know me better; because people learn as they go along but it's all too late, they've got involved with it. So many people are trying so hard to get themselves nervous on this film. I keep trying to convince myself that it's still a little film. This isn't a difficult film really, but because they've seen BRAZIL and MUNCHAUSEN they want to work on something like that. And when I say, 'No, we really just need that little thing,' they don't really believe it. Q: Are the people on this film trying to make this like BRAZIL and MUNCHAUSEN when it's not? Gilliam: Well at times it feels like that; I mean, I keep telling people it's . . . I don't know. I've given up trying to understand anything!

Previously published in Millimeter Magazine, March 1991.

| |||||||||||||||||

copyright 1990, 1991, 2009 by David Morgan

All rights reserved.

The last couple of days were very silly where we're doing a close-up of Jeff in front of Carmichael's townhouse, against those stairs which were built in California, with all of Madison Avenue behind us, with buses. The noise is unbearable, it's ruining sound takes, and I'm shooting stuff like that. And I used to laugh at people who did things like that, it's ridiculous; you could do that close-up in L.A. — just bring the wall back. But we end up doing it because everybody's fired up, you've got to do it. Yesterday we did [close-ups] with the Knight on Fifth Avenue, and what you see on film, I'm not sure if you know it's Fifth Avenue, which is very, very bad. But it's to do with the fact that you get away with it, is why you do it.

The last couple of days were very silly where we're doing a close-up of Jeff in front of Carmichael's townhouse, against those stairs which were built in California, with all of Madison Avenue behind us, with buses. The noise is unbearable, it's ruining sound takes, and I'm shooting stuff like that. And I used to laugh at people who did things like that, it's ridiculous; you could do that close-up in L.A. — just bring the wall back. But we end up doing it because everybody's fired up, you've got to do it. Yesterday we did [close-ups] with the Knight on Fifth Avenue, and what you see on film, I'm not sure if you know it's Fifth Avenue, which is very, very bad. But it's to do with the fact that you get away with it, is why you do it.